Tom Cramer’s

Works on Paper: The Framework for Drawings in Wood

by Linda Brady Tesner

Such is the triumph of Tom Cramer’s companion exhibitions at the Mark Woolley Gallery and Woolley’s new space at the Wonder Ballroom in northeast Portland. Cramer’s drawings, exhibited here for the first time ever, are critical signifiers for this artist’s creative process in crafting his well-known carved wood panels. For those who remember his roughly hewn chainsawed totem poles, the delicacy of Cramer’s drawing oeuvre may come as a surprise.

The earliest works in the exhibition date from 1973, from Cramer’s childhood, really. Several of the smaller works are line drawings that Cramer made at the tender age of 14, a time when the angst of puberty was compounded by his parents’ divorce. Cramer recalls putting on earphones, listening to music, and drawing in order to escape and cope. Cramer’s mother is an accomplished musician, a piano teacher and church organist; music was ever-present in the Cramer household. Rather than listen to “zit music,” as his mother derisively called the rock and roll of the mid-1970s, Cramer absorbed classical music or jazz from J.S. Bach to Charlie Parker—plus maybe the Beatles or the Doors—as he drew, birthing a lifelong love of music (elements of which appear frequently in the drawings).

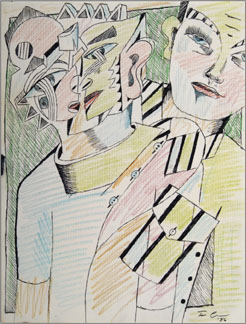

Duet

These early drawings are marvelously

simple line illustrations, mostly figurative uber-doodles limned in the

thin contour of a Rapidograph pen. Influences of surrealism and cubism are

evident; a single face may have two sets of eyes/nose/mouth; limbs are deconstructed,

and the figures conjure no sense of weight in their spaceless plane. Cramer

credits John Lawrence, his art teacher at Catlin Gabel School, for introducing

him to Picasso, Paul Klee, and German expressionist artists—influences

that remain with Cramer today.1

As Cramer moved into making sculpture, both freestanding and reliefs, he

continued to use drawing to work through ideas. Many of the works in this

exhibition are graphic explorations of themes that have always intrigued

this artist: the notion of an inner landscape, the contradictions and polarities

inherent in the human psyche, the ambiguousness of sexuality, the surrealism

of the subliminal. A drawing (Duet) from 1986 is a good example.

In this ink line drawing with colored pencil, Cramer seems to have bifurcated

the dual persona of one human being. A realistic figure on the right, wearing

a button-down shirt and a staid expression, contrasts with a more fantastic

head and torso on the left, an angular visage with three eyes, an exaggerated

ear, and geometric protuberances. Cramer made this drawing, like most of

his graphic work, on charcoal paper, so the pencil dragging across the paper’s

tooth adds texture to the line drawing—as with the artist’s carvings

into wood, where the grain enlivens the carving surface.

Other drawings are more overtly graphic, a nod to a period when Cramer was

known for eye-popping posters, T-shirts, and the numerous “art cars”

that one unfortunately sees less and less frequently on Portland city streets.

Cramer’s vocabulary includes the squiggly lines, checkerboard patterns,

zigzag forms, and sun/star bursts one expects to see in his earlier relief

panels. In many of these drawings, Cramer uses patterns of hatchings and

stylized darts to suggest volume. One can imagine the artist’s pen

striking at the paper surface—a process not far removed from the repetitive

chiseling needed to render Cramer’s wood pieces.

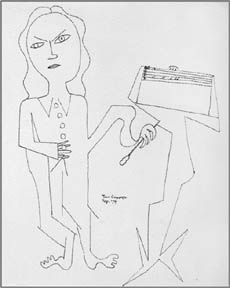

Conductor 1974, 4 x 7, collection Gus Van Sant

As with his past sculptural totemic

figures and carved historic portraiture, the figure has been a prominent

constant in the past 30-plus years of Cramer’s drawing practice. His

human figures combine with all manner of other icons idiosyncratic to the

artist—a plant still life, a musical instrument (keyboards and stringed

instrument necks appear frequently), geometric patterns, or robotic pipelike

elements. The people might have both male and female organs, and frequently

have duplicate eyes. Sometimes his figurative drawings, in their disjointed

stream-of-consciousness compositions, remind one of the “Exquisite

Corpse” drawings of the surrealists—those collaborative pieces

where a page is folded over and over, and several artists contribute one

section to the composition without knowing what the other artists have already

drawn. Surrealism, from the French, literally means “beyond realism,”2

of course, and Cramer’s work fits this description.

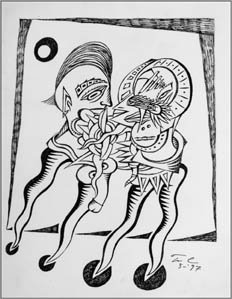

Rendezvous

1997, 12 x 9

In the past 10 years, Cramer’s

drawings have become even more resolved, echoing the maturation of his wood

pieces. Two pilgrimages to India have had a pervasive and lasting effect

on Cramer’s work. The use of precious metal gilding, the mandala-like

compositions, and symbols intrinsic to Eastern religion evoke a more spiritual

expression in Cramer’s most recent work. Iconic emblems and ideograms

are also present in his most recent drawings, as in the 2005 Menagerie

illustrated here. In this dreamlike image, one finds a lotus blossom, a

scarab beetle, a serpentine line ending in a spiral, a dog and a horse (both

ancient symbols of soul companions, to help the dead sense the road to afterlife),

evil-eye forms, and even three vertical undulating lines (known to symbologists

as a sign meaning “an active intelligence”3).

Images such as these suggest that Cramer, while not necessarily leaving

the realm of the psyche, is also investigating the realm of the spiritual.

1Cramer

also credits an early meeting with Clifford Gleason and, in the 1980s and

’90s, the work of Milton Wilson as important influences on his work.

2Tom Cramer has mentioned his admiration for the surrealist artist André

Masson, and many of Cramer’s drawings share an affinity with Masson’s

“automatic” drawings, which involved the free movement of the pen

line with no advance notions of the finished work.

3Liungman, Carl G. Dictionary of Symbols (1991), p. 88.